Camagüey.– The stone I hold in my hand — white, opaque, tiny — was once a drop of water. That’s what the woman who cared for Eduardo Labrada Rodríguez during his final years told me. In the deepest darkness, where almost nothing changes, time becomes an architect. A drop falls on the same spot, with infinite patience, until it turns into mineral. That is the logic of caves. That was him, a man who walked drop by drop, word by word, without shouting, without hurry, without the need to impose himself on anyone. Only perseverance. Only truth.

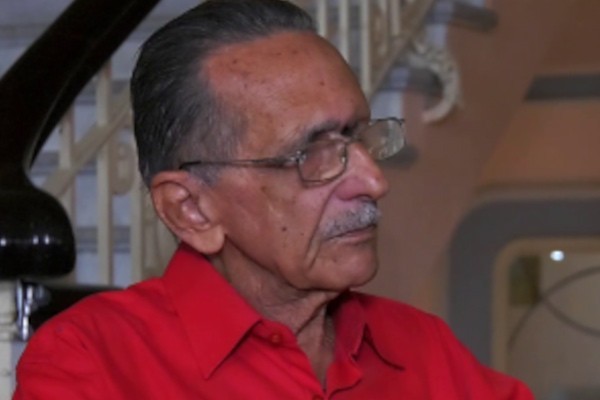

A few hours ago, he passed away at the age of 88, after an illness that gradually weakened him physically but never broke his will to live.

His colleagues at Adelante had been on edge for weeks. He, who always seemed stronger than the wear of time, had entered that zone where predictions no longer help. And yet, he still had appetite. And yet, he smiled when a visitor arrived. When I went to see him, his face already unfamiliar, he was still himself: he asked me about the newspaper, the work, the city; I almost unconsciously waited for him to call me Trigueñita again, and though this time he did not say it, he knew perfectly well who I was.

That drip stone I keep is the thread that lets me enter another cave: that of his memory. Labrada always loved the earth’s innermost parts: the abysses, the damp chambers where time breathes slowly, the millenary formations that taught him every story has an origin. Maybe that’s why he was a speleologist, or maybe that’s why he was a journalist: because he was always searching for the root.

At Adelante, he was the oldest colleague. He arrived back when the first newspaper was made by Journalism students, as he himself proudly recalled.Since then, he was a constant presence, a way of being that blended rigor, curiosity, and a disarming humility.His section Catauro, nurtured over the years, was a laboratory of discoveries: rare words, old customs, creatures of local speech and collective imagination.

Labrada rescued, like few others, the archaeology of the everyday.

But he also had a jíbaro dog: Turán, protagonist of stories, companion on walks, unwitting character in chronicles that he told without pretension, with clean humor. With Turán, one understood that Labrada explored the world with the same attention others give to reading a classic: every sign, every stranger, every tiny event was a story in the making.

As if that weren’t enough, when blogs became fashionable and many of us only started one because we were required to, he opened three. He dedicated one to unusual texts traced in the old Camagüeyan press; another to nature and environmental heritage, because he was a delegate for the Antonio Núñez Jiménez Foundation. There is an identity statement: the blog Cartacuba. That name says a lot: the Cartacuba is small, beautiful, endemic; it doesn’t need showiness to be unforgettable. Like him.

He granted me one of his last interviews when he was working on a report about the heritage collection of the Julio Antonio Mella Provincial Library. It was one of the few times I saw him truly wounded.

He spoke with the calm of someone who deeply loves what they defend, but beneath every sentence vibrated a concern: that Camagüey’s memory was crumbling before our eyes. He would list treasures that could no longer be touched, and recount the unusual story of his own lost book — La prensa camagüeyana del siglo XIX, published in 1987. That copy he himself had donated and inscribed, which one day he found on a secondhand book sale table, as if it were an orphan. He recovered it, yes, but with the sadness of knowing that something deeper was failing.

Labrada knew the Library like someone familiar with a beloved cave: he could walk through it without looking, could point out shelves where forgotten chronicles, political cartoons, the shocks and joys of Camagüey across centuries, slept. He then told me about the importance of preserving, teaching the youth, opening doors, guiding. For him, memory was a living territory: something breathing. Something that could be lost.

And he added, almost with a sigh: “There lies the history of Camagüey... stories we still do not know.” He didn’t say it as a complaint: he said it as a call. Now I feel those words are also a legacy.

Labrada’s life was like that: a drop after another on the stone. A silent consistency. An ever-watchful eye. A heart that never stopped asking questions. A journalist who believed history is never fully told. A man who nourished libraries, dogs, blogs, colleagues, friends, students, readers. A Camagüeyan whose voice had the texture of old newspapers.

On the night of November 27th, Adelante lost its most popular journalist, the one readers sought not only for his byline but for the trust he inspired. For years, he diligently maintained the sections dedicated to readers’ letters, a space where he learned—and taught—that a journalist cannot solve people’s problems but can clear the path toward a solution. People wrote to him out of urgency, sometimes even desperation, and he did not avoid conflict: he courageously pointed out the failing institution or agency and defended, case by case, the dignity of the ordinary citizen. Perhaps because of that sensitivity toward others, he also became a neighborhood delegate, where his professional ethics became community ethics: listening, supporting, guiding.

I regret that despite so many insistent efforts and accumulated merits, we never managed to have him receive the José Martí National Journalism Award for Lifetime Achievement. It was an accolade he deserved without question, but it never came. Even so, he received the greatest reward: the deep respect of his readers, the gratitude of those who found in him a voice that would not be intimidated and a hand willing to guide. His legacy needs no diploma; it has been sown among the people, where he always wanted his stories to grow.

The stone I hold in my hands today was born from a persistent drip, just like him. I don’t know how many years it took to form, but I do know that its light, although faint, does not get lost. I imagine that Labrada must have picked it up in a damp cave, perhaps after hours of walking, and that by keeping it, he wanted to bring with him a piece of the world where the deep pulse of the earth is felt.