On November 25, 1956, the yacht Granma set sail from Tuxpan, Mexico, with 82 expeditionaries on board. Leading the group was Fidel, and after a little more than a year of coordination with the 26th of July Revolutionary Movement in Cuba, exile, military preparation, and adjusting essential details, they were determined to fulfill their pledged promise that in 1956 they would be free or martyrs. After the journey, the landing on the Cuban coast on December 2nd took place under difficult conditions due to the characteristics of the area.

The Commander in Chief, Fidel Castro Ruz, recounted this in the prologue he wrote for the book by fighter Georgina Leyva, *History of a Liberating Feat*:

“When the Granma reached Cuba with 82 men on board—when it could comfortably hold 12 crew members—it was two days later than planned and, by sheer miracle, did not sink over more than a thousand miles because of the stormy 'nortes' at the time, or close to 10 or 12 miles from the coast because of the tyranny’s gunboats. One of our fighters had fallen into the water while on watch; no one knows if by accident or exhaustion, and it took us at least two hours to rescue him. He was responsible for steering the boat. The chief navigator, one of the navy officers with the rank of Commander, displaced by Batista, had gladly offered to accompany us. The problem was that at that critical moment of the landing, he forgot the lighthouses that indicated the exact route for entry through that dangerous area, near the lighthouse located at the southwestern tip of the former Oriente province.

The Granma had already made three circles and the ex-military man was requesting a fourth when dawn was breaking, and the sun was about to rise. I said to him with evident irritation, ‘Are you sure that is the coast of Cuba?’—more to annoy him because, obviously, it was our country—‘Head full steam toward that point until the bow touches the shore.’ Having done so, an old comrade, René Rodríguez Cruz, thin and short, without any load, went down the bow. After him and confident, I went down with rifle in hand, ammunition belt full around my waist, and a backpack weighing more than 60 pounds, including a submachine gun with many bullets and other essentials. But as I moved, my legs sank deeper and deeper until I almost drowned. Finally, helped by other comrades, I managed to get out with rifle, ammunition belt, canteen, full gear, and began to walk. Raúl remained on the ship until he took out the last weapon we had as a cache, and we immediately began to march. It took us two hours to cross those swamps. The incredible thing is that we were just a few meters from a pier, perfectly visible—if the boat had taken the correct route.”

If you need any further help with translation or context, feel free to ask!

Army General Raúl Castro Ruz, then a captain and chief of the rear platoon, reflected this in the campaign diary he wrote during the intensity of those days:

"At around 5:30 or 6:00 a.m., for some reason, we took a straight line and ran aground in a muddy place, entering the worst swamp I have ever seen or heard of. I stayed until the very end trying to take out as many things as possible, but afterwards, in that damn mangrove, we had to abandon almost everything. More than four hours scarcely stopping, crossing that hell. Upon reaching almost firm ground, our group encountered Luis Cr.² who informed us that they already had a bohío and a farmer located. It was December 2. Along the way, I found comrades almost fainting, and when I headed to the bohío with Armando M.³ we heard a series of cannon shots and machine guns, probably directed at our abandoned boat, the Granma.

I also received the unpleasant news about the loss by misplacement of 8 comrades⁴... We waited around the area until well into the late afternoon to see if the comrades would show up, with a plane constantly circling and starting to machine-gun the bohío where we thought of eating something, about 2 kilometers from us.

We advanced through a thicket of tall grass but with few trees. We had to keep lying down on the ground frequently. That day we had not eaten any food. We wandered around completely lost several times until, using the directions from the first farmer, we were able to get somewhat oriented. We all slept exhausted that night and without eating. (74 men). An immense ordeal that December 2⁵."

In those difficult circumstances, the group of expeditionaries gathered and reached Alegría de Pío, where on December 5, under enemy attack, the detachment dispersed. Some managed to regroup and continue toward the Sierra, as planned: this was the case of the groups led by Fidel, Raúl, and Almeida, who reunited days later at Cinco Palmas; others took routes whose only option was to try to evade the encirclement and reach the plains to try to save their lives; and others were captured and vilely murdered.

Regarding the reunion of Fidel and Raúl at Cinco Palmas on December 18, it is known that when the revolutionary leader was informed that a young man claiming to be his brother was located and was shown Raúl’s Mexican driver’s license, he was emotionally moved by the news but also cautious. He told Primitivo Pérez, the farmer who brought the news: “I am going to give you the names of the foreigners who came with us… You memorize these names, and you go back and ask him to say them to you, with the nicknames. If he says them all correctly, that is Raúl.”

And so it was. And the encounter took place that forever sealed the historical certainty that “every Alegría de Pío has its Cinco Palmas.”

But who were those four foreigners who came on the Granma? The Dominican Ramón Emilio Mejías del Castillo, Pichirilo; the Italian Gino Doné; the Mexican Alfonso Guillén Zelaya; and the Argentine Ernesto Guevara de la Serna, Che.

The four foreigners of the voyage of the century...

After the landing on December 2nd, and the dispersal from Alegría de Pío, the four foreign expeditionaries survived, although only Che remained with the group that stayed in the mountains – he was in Juan Almeida Bosque’s group – where he grew and became a giant, as he was the first rebel promoted to the rank of commander and appointed leader of the second guerrilla column, decisions made by the supreme leader already in 1957... his feats in 1958 and his actions after 1959 became known worldwide.

As for Pichirilo and Gino, they managed to evade the encirclement after the dispersal and saved their lives. Protected by members of the 26th of July Revolutionary Movement, they succeeded in leaving Cuba but remained connected to the fight against the tyrant Fulgencio Batista, with the intention, on several occasions, of reuniting with their comrades in the Sierra, although they did not succeed.

Zelaya, the Mexican, was captured and sentenced to six years in prison and, after thirteen months, deported to his country.

Zelaya, as well as Pichirilo and Gino, had Mexico as their initial destination, something at that time closely linked to the work of that country’s ambassador in Cuba, Gilberto Bosques Saldívar, who saved the lives of many revolutionaries who sought asylum at the Mexican embassy. This ambassador was appointed by the Mexican government of Adolfo Ruiz Cortines to work in Cuba and remained in our country during the period of insurrectional struggle and some years after the triumph of the Revolution.

After the revolutionary victory, Pichirilo and Zelaya returned to the Island, while Gino did not do so until many years later, although he always followed Fidel’s cause from his modest position, feeling himself a part of it.

Pichirilo

Ramón Emilio Mejías del Castillo was born on February 12, 1922, in San Pedro de Macorís, into a family of fishermen and sailors who were heavily persecuted by the dictator Rafael Leónidas Trujillo. Because of this, he was forced to leave his homeland at a very young age.

He traveled through several Latin American countries and enlisted in the Cayo Confites expedition organized in Cuba to fight against the quisqueyano tyrant.

It was there that he met Fidel, a university student who was in his battalion and, recognizing his skills in handling boats and his love for freedom, later called him to be one of the helmsmen of the yacht Granma.

Thus, Pichirilo entered the history of the Cuban Revolution.

After the landing, he took refuge in the Mexican embassy and left for that territory, from where he collaborated in the struggle. Later, for the same cause, he moved to Venezuela and witnessed the revolutionary victory there; for that reason, he traveled to the island and remained there until 1963, when he decided to return to his beloved land, now under the government of the venerable revolutionary Juan Bosch.

During the 1965 U.S. invasion of the Dominican Republic, known as the April War, Pichirilo fought against the invaders as part of the army defending the legitimate Constitution. He was recognized and feared by his adversaries, as he was a very brave man who always faced matters head-on.

Once the war ended, with unfortunate consequences for the defenders of Bosch's government and supporters of Francisco Caamaño's drive, a kind of reckoning began against all those who had been part of the "constitutionalists," including Pichirilo. For this reason, he was treacherously shot on August 12, 1966, and died shortly afterward from his wounds. His loss caused consternation among the people, who recognized him as one of the heroes of the April struggle.

Gino

The only European who came on the Granma was the Italian Gino Done, born in San Biaggio di Callalta, Treviso, on May 18, 1924. A partisan who fought in World War II and whose experience helped him be accepted as an expeditionary of the group organized by Fidel.

After the war ended, he arrived in Cuba in the 1950s, where he worked in a crew building the highway of the southern circuit, Cienfuegos-Trinidad. There he met Norma Turiño, a young woman from a well-established family, whom he married and with whom he became involved in revolutionary tasks in Las Villas.

He worked in Havana and Trinidad until he was called by the 26th of July Revolutionary Movement to join those training in Mexico to come fight in Cuba. Gino, a lover of freedom and a witness to the difficult situation of the people and the oppression by the dictator Fulgencio Batista, quickly said yes.

Once in Mexico, he served as a messenger for the Movement, and his combat experience earned him a place among the selected. After the dispersion of Alegría de Pío, he managed to escape. In Las Villas, he learned that Fidel was alive and still in the mountains but was unable to return to the mountains and come back alive. He had to leave the homeland, and several times he tried to come back and join the war but was unable due to various circumstances.

In the Office of Historical Affairs, documents belonging to Gino Doné are preserved. One of them is a letter written in Mexico to Pichirilo, who was also exiled in that country.

Veracruz, July 10, 1958

My dear friend:

I arrived this morning. There are many ships in the port, mostly Norwegian, which is a pleasant sight. I have already been to the company and they promised to take an interest, so now all I can do is wait.

The Cuban gentlemen have not yet been located, but I will try to find them today.

The weather here is pleasantly warm and I’m already feeling great. I sent you a postcard from Puebla. I spent two days there. It is very interesting.

Helia would love it. Don’t miss the chance to go if the opportunity arises.

I am doing everything possible to resolve our matters in the best way and I hope to receive news soon. I will not fail to write to you tomorrow or the day after. Everything here is the closest thing to Cuba, which is enough to feel better than in Mexico City. I miss you all very much but I trust I will see you soon and be able to show you all my affection.

Yours,

Gino Doné

After January 1, 1959, once established in the United States, he tried to return; however, a mistaken communication regarding his expired papers and his decision not to reveal his identity as a Granma expeditionary led him to adopt a distant and discreet stance, although he remained informed about the developments in that Island that had forever captivated him.

In July 2006, he reunited with the Commander-in-Chief in the province of Granma, where he had landed fifty years earlier. As he used to say: “To Fidel, fidelity.” It was the guiding principle of his life and of the work he carried out in favor of Cuba from the moment he returned to Italy. He died on March 22, 2008, and his last wish was for his ashes to rest in Cuba, where they have been since December 2, 2023, alongside those of other heroic expeditionaries.

Zelaya

The Mexican Alfonso Guillén Zelaya was the only one from that sister nation who came on the Granma, among so many who would have wished to. He was born on August 9, 1936, in Coahuila.

In 1955, when he heard Fidel speak in the Chapultepec forest, he was deeply moved and decided to collaborate with the young man who spoke so passionately about freedom, the dreams of a people, and the history of Latin America. That is how he joined the troops preparing to fight Batista's dictatorship. Due to his excellent performance in the training, he was selected. After the Granma landing, he was captured and deported to his country, although he continued collaborating: he raised funds for the fight against Batista and even performed as a magician in Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador.

On January 2, 1959, he returned and was granted the rank of captain in the Rebel Army. In 1963, he worked with Che on projects for the Ministry of Industries and, among other roles, also served as an advisor in the Ministry of Light Industry in 1967; vice president of the Cuban Institute of Friendship with the Peoples in 1979; and in 1991, he was appointed advisor of International Relations at the Ministry of Education until April 22, 1994, the date of his death at an event in his native Mexico.

Zelaya also decided that his remains should rest in Cuba, alongside his comrades, and this was honored.

The Mexican was one of the youngest expeditionaries — he was twenty years old in 1956 — when he fell in love with the Cuban cause and made it his own, and our people embraced him forever.

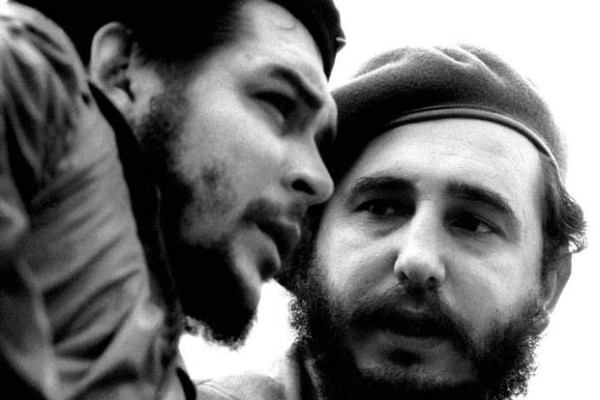

Che

The most well-known of the four foreigners who came on the Granma, and of the Rebel Army and the Revolution in all its dimensions, is—without a doubt—Che, the Argentine Ernesto Guevara de la Serna. Our Che.

Born on June 14, 1928, in Rosario, he became one of the leaders of the Cuban cause, and his example and dedication made him one of the most beloved and admired heroes. His fall in Bolivia, fighting for the emancipation of the men and women of Latin America, made him a global paradigm for rebels and generations from different eras up to today.

And perhaps, because of his leadership and for being the mythical chief of the Revolution who was not born in Cuba, the other expeditionaries who shared that same condition always maintained a connection with him.

In the case of the Dominican Ramón Emilio Mejías del Castillo, he set sail in 1963 to return to his Dominican homeland on a boat and, according to some witnesses, his journey back home was known to Che. Zelaya, for his part, worked with Che, which made him a witness to the leadership style of that young Argentine, his dedication to the cause, the example of a true communist, and an authentic revolutionary school. In Gino’s case, his connection with Che dates back to the days in Mexico, during the preparations for the expedition. With that disciplined, tough Argentine who spoke about communist ideas and who would serve as a combat medic on the expedition, he had the opportunity to talk, and Che seemed very curious, interested in learning about Italy, about the period of fascism there, and agricultural reform. Gino told him about his experiences, and at some moments the South American expressed his desire to travel to those lands.

After the landing, when crossing the mangroves Che was in poor physical condition due to asthma, Gino went back to help him, and thanks to that, Che was able to join the rest of the group. On the other hand, by the advanced stages of the war, when the Italian returned to try to join the fight in the mountains, he did so in the Las Villas area, where his wife and close contacts were, and also where Che was in the Escambray. And although his joining the rebels did not materialize, had it done so, it would have been with the troop of his friend the Argentine.

Guevara was a kind of center and support, of respect and admiration for that small group of internationalists who, moved by Cuban history and their leader Fidel Castro Ruz, had a very clear concept of internationalism and the struggle for any people in the world.

The stories of those eighty-two men, united by a common cause, sometimes go unnoticed in the larger scope of history. However, on this date, we share the stories of those four brave men who loved our homeland as their own and gave everything for it, for our Revolution, and for our people. For that reason, they are also Cubans who risked their lives for the common good.

These names: Pichirilo, Gino, Zelaya, and Che, are part of our history, of the rebirth of hope... With them, the most beautiful and revolutionary spirit of the Dominican Republic, Italy, Mexico, and Argentina came with us on the Granma, in the journey of the century, that of our Revolution...