The "three crazy Cubans" are unleashed. For years, Mario Díaz-Balart, María Elvira Salazar, and Carlos Giménez have presented themselves in the United States Congress as a cohesive Cuban-American bloc: a hardline stance against governments they label as "totalitarian," applause for sanctions, and public defense of draconian measures that are hardly admissible in a truly democratic context.

In recent months, they have shown an almost monolithic unity in support of Donald Trump and his agenda, to the point that the nickname circulates among their colleagues as a synthesis of this group's role.

In Congress, they are an inflexible and strident trio that helps set the tone for South Florida and pushes towards confrontation in the hemisphere.

Within that trio, however, there is one especially illustrative case: Carlos Giménez's obsession with Mexico. The most recent evidence came this Tuesday in an interview published by The Floridian, where Giménez backed Donald Trump's executive order that classifies illicitly manufactured fentanyl as a “weapon of mass destruction” (WMD).

His praise did not stop at prevention, treatment, harm reduction, or financial networks. He did what he usually does: turn the problem into a war report. He said the cartels are "probably worse than Al-Qaeda and ISIS," and when speaking of those who “adulterate” drugs with lethal doses, he pointed to Mexico: “In my mind, it’s Mexico; the Mexican cartels are the ones mixing it.”

Calling fentanyl a “WMD” reconfigures the framework from public health and organized crime to the exceptionalism of war. In that logic, Mexico ceases to appear as a complex partner with whom to coordinate actions—with inevitable tensions—and instead becomes a primary culprit to whom violence, death, and threat are attributed by association. The country is reduced to a functional stereotype, a cartel territory. That framing does not attempt to understand the full circuit of the phenomenon; it seeks political legitimacy to harden positions and to point to a guilty "outside."

The outburst of the “crazy Cuban” is already a pattern in his political discourse. Giménez has spent years installing Mexico as a permanent villain in his hemispheric script. When he talks about drug trafficking, the argument is not limited to pursuing criminal networks but drifts toward broad political accusations, as if Mexico’s institutional complexity, transnational corruption, or even U.S. market demand were secondary details compared to the utility of pointing to a culprit.

The obsession becomes clearer when Giménez tries to transfer the siege against Cuba to the heart of the relationship with Mexico. At the end of October, he sent a letter to senior administration officials requesting that the renegotiation of the USMCA/T-MEC treaty be used to force Mexico to “end its troubling relationship” with the Cuban government, suspend oil shipments to Havana, and stop what he calls “trafficking” of Cuban doctors, presented as "modern slavery."

In the same package, he accused Mexico of "instrumentalizing" migration to the United States and linked that accusation to the Cuba-Venezuela axis of his agenda. He went as far as to claim that the commercial proposal from Claudia Sheinbaum's government is an attempt to turn the main regional economic agreement into a mechanism for ideological alignment.

By pointing to Mexico as the place where the "poison is mixed," Giménez turns a discussion about organized crime into a national threat and a geopolitical accusation, useful for sustaining a pressure agenda. Mexico ceases to be an interlocutor and becomes a "channel" that must be closed: fuel, medical cooperation, diplomatic positions; everything can be relabeled as "complicity" with Cuba.

Giménez’s obsession with Mexico, then, is less a security policy than a policy of expanded containment. It does not describe the complexity of a transnational criminal market; it supports a script where Cuba is the center and Mexico is the most useful field of pressure.

If this logic prevails in Washington, any serious debate about cooperation, public health, and shared responsibilities will be subordinated to the dramaturgy of this psychopath.

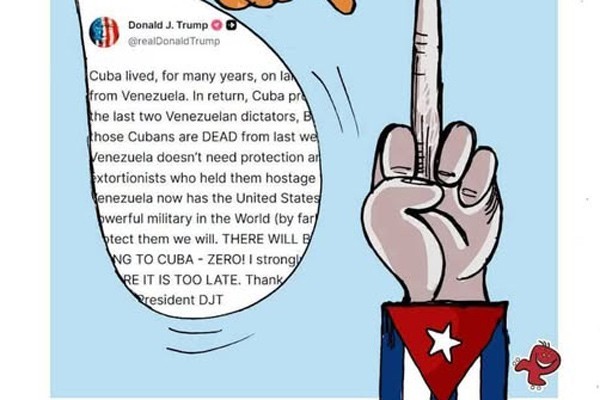

In the photo: Congressman Giménez (Cubadebate Archive)

(Taken from La Jornada)